by Emilio DE CAPITANI

Parliamentary committees venue for real negotiations between political groups…

This week in its constitutive session of the new parliamentary term, the European Parliament will elect its President, the Bureau, the College of quaestors and, most importantly, will decide on the number and competencies of its parliamentary committees.

Less visible than the EP President, however, parliamentary committees are the real forum for legislative negotiations through which the European Parliament plays a decisive role in shaping EU policies. In the absence of a real European government (since the Commission is still far from fulfilling this role), and in the absence of Majoritarian Legislative Pact among EU political families (as is the case in Germany, for example), a political majority on a legislative proposal is formed dossier by dossier within the framework of the parliamentary committees. As a rule, once an agreement is reached committee level, the text is approved by the plenary, as is the case, moreover, in most of national parliaments.

… and with the Council and the Commission through the so-called “Trilogues.”

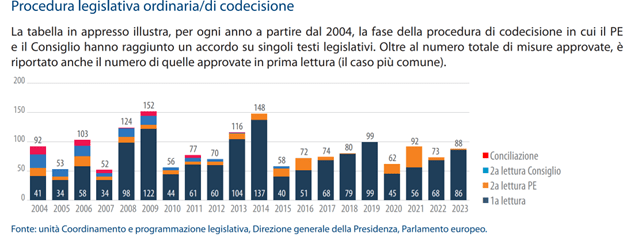

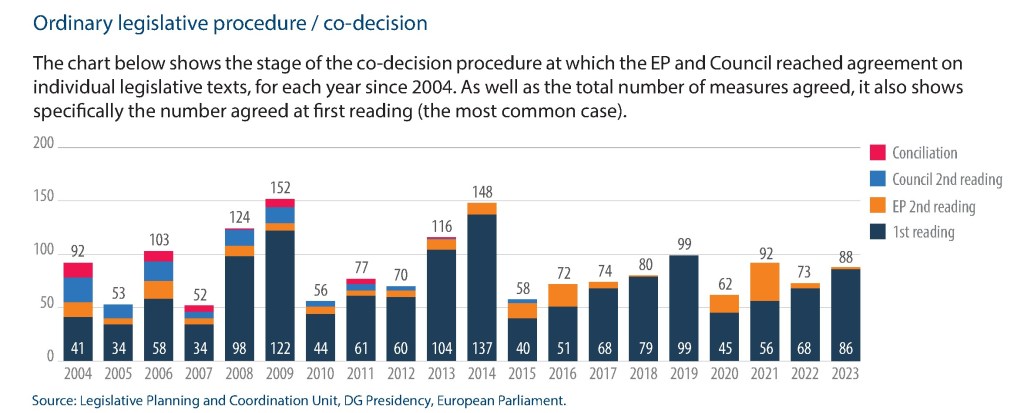

However, the real qualitative leap in the role of the European Parliament’s committees, has occurred since the early 2000s with the expansion of the practice of so-called “legislative trialogues,” so called because the dialogue between the two co-legislators, Parliament and Council, is now increasingly joined by the Commission. The success of “legislative trialogues,” which have now become the rule in the Union’s legislative decision making process, stems from the fact that even though the Treaty (Article 294 TFEU) provides that a legislative proposal may be adopted through as many as three “readings” by Parliament and the Council, it also provides possible shortcut because the legislative procedure can be concluded as early as when the Parliament adopt its first “reading” provided that the Council accepts Parliament’s amendments to the Commission’s proposal.

Hence the interest of the parliamentary committees not only in agreeing on a text that gathers a majority among the political forces but which may also be acceptable to the Council. To achieve this result, after a provisional agreement is reached inside the Committee this provisional text is submitted to the Council which may submit its own “mandate” so that , starting from these draft a “trialogue” is organized, which, depending on the difficulty of the subject matter, can also last several months.

During that period, members of the parliamentary committee delegation work directly with the Council presidency in order to reach an agreement on each word of the legislative proposal that satisfies the two institutions. The agreement is then submitted to the Parliamentary Committee which endorse it and transmit to the EP plenary which approve it with a single vote. After the endorsement by the Council the legislative procedure is successfully concluded.

The success of this practice, which is only implicit in the Treaty, is proven by the table below, which presents the stage of adoption of European legislative procedures during the period 2004-2023 and which shows that first-reading agreements have become the rule since several years from now.

As de facto, the text agreed in Committee is adopted as such and is not amended by the Plenary the parliamentary committees have become the exclusive place where legislative political negotiations take place and agreements are dealt with (even though from a formal point of view the text voted by the Plenary is still defined as the EP’s “Position”)[1].

Looking from a quantitative perspective : which Committees are most relevant ?

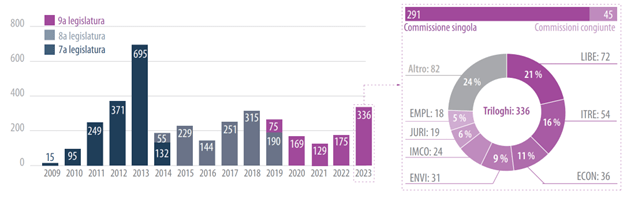

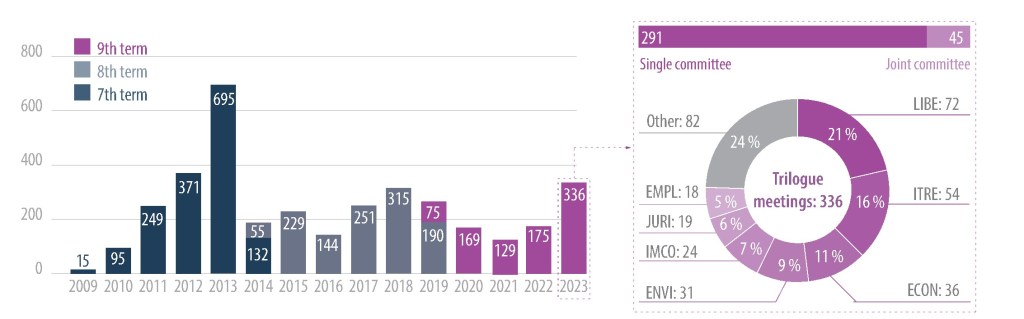

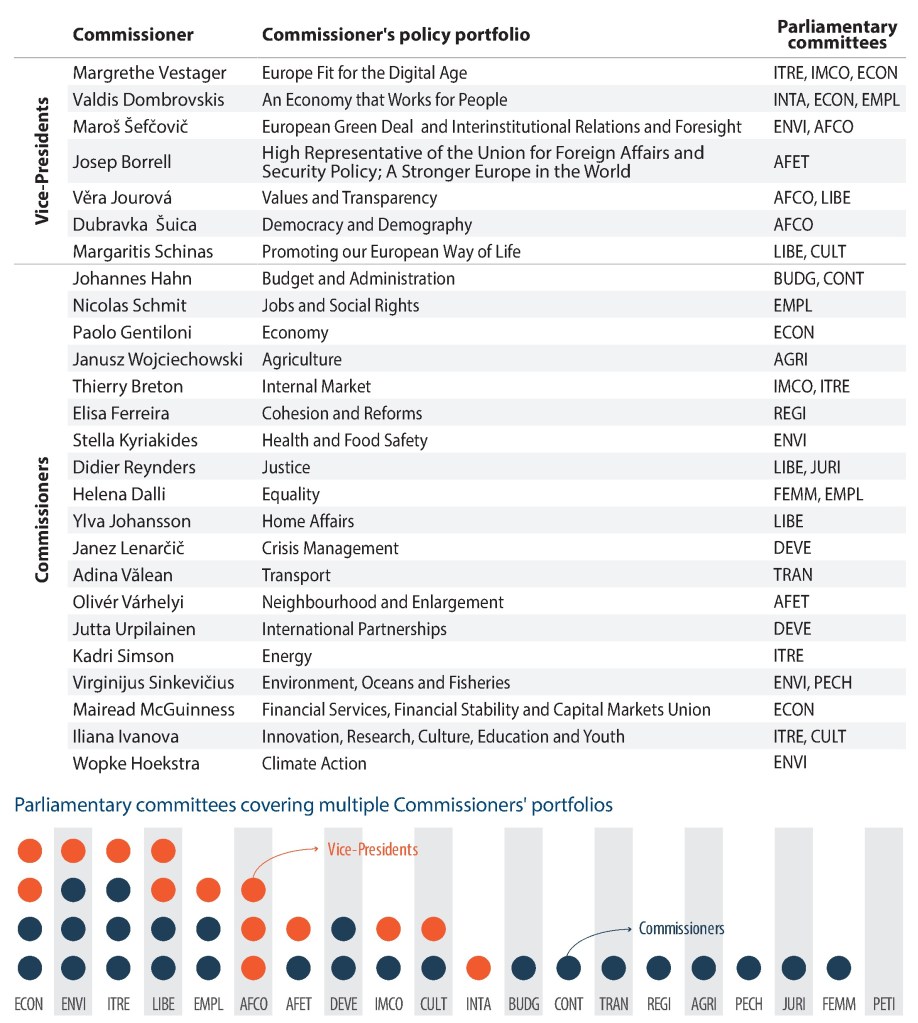

It is important to note that not all 20 parliamentary committees have equal legislative weight. Rather, only seven committees cover more than 75 percent of the legislative trialogues and they are the following LIBE (21 percent) ITRE (16 percent), ECON (11 percent) ENVI (9 percent) IMCO (7 percent) JURI (6 percent) and EMPL (5 percent).

Looking from a qualitative perspective : how EP Committees competencies fit with the ones of the other two “corners” of the “legislative triangle” (Commission and Council) ?

In an interinstitutional perspective the most challenging question is how the EP Committees competencies are mirrored on side of the Commission and of the Council side. Clearly, the EP, the Council and the Commission have a singular legal entity but they are also organized internally following different domain of competences.

As far as the Council is concerned it meet in different configurations according to the subject-matter dealt with. The list of Council configurations, other than the General Affairs and Foreign Affairs configurations, has been adopted by the European Council acting by a qualified majority on the basis of art.236 (a) TFEU. The current 10 Council formation are the following :

1. General affairs ( see also art.16.6 TEU);

2. Foreign affairs (see also art.16.6 TEU);

3. Economic and financial affairs ( including Budget );

4. Justice and home affairs ( including Civil Protection );

5. Employment, social policy, health and consumer affairs;

6. Competitiveness (internal market, industry, research and space) ( including Turism );

7. Transport, telecommunications and energy;

8. Agriculture and fisheries;

9. Environment;

10. Education, youth, culture and sport(including Audiovisual affairs).

It is worth noting that the relations between the EP and the Council even after Lisbon are still rather formalistic, notwithstanding these two institutions are jointly responsible for the legislative and budgetary functions (see art 14.1 and 16.1 of the TEU), are bound to legislative transparency (art.15.2 TFEU) when debating draft legislative acts as newly defined by art.289.3 TFEU.

Bizarrely and notwithstanding the daily cooperation in the framework of hundred of trilogues the two institutions still behave like Chess players instead of acting in a spirit of sincere cooperation as required by art. 13 TEU.

The different treatment reserved by the Council to the European Commission compared with the relation with the other co-legislator is appalling[2]. Far from acting as the second chamber of a bicameral parliament the Council still hide its legislative strategy to the other co-legislator and to the national parliaments as if it was not co-responsible with the EP of the legislative outcome before the European Court and the European Citizens. Surprisingly the EP and Council have not yet updated their pre-Lisbon agreement on the co-decision procedure [3]

On the Commission side the internal organization is defined at the beginning of the legislature by taking in account not only the missions outlined in art. 3 of the Treaty, the EU Strategic agenda as adopted by the European Council, but notably the political priorities agreed by the Commission President with the European Parliament. This special relation between the EP and the Commission is framed not only in the Treaties but also in an interinstitutional agreement [4] which should be updated together with the latest version of the “Better Law Making” interinstitutional agreement [5]

That having been said a new interesting development may arise in the relation between Commissioners and Parliamentary Committees art 2 of Annex VII of its Rules of procedure, which will enter into force this week. According to that article :

“1. Parliament shall evaluate Commissioners-designate based on their general competence, European commitment and personal independence. It shall assess knowledge of their prospective portfolio and their communication skills.

2. Parliament shall have particular regard to gender balance. It may express itself on the allocation of portfolio responsibilities by the President-elect. (emphasis added)

3. Parliament may seek any information relevant to its reaching a decision on the aptitude of the Commissioners-designate. Parliament expects Commissioners-designate to make full disclosure of information relating to their financial interests. The declarations of interest of the Commissioners-designate shall be sent for scrutiny to the committee responsible for legal affairs.”

Will the EP Plenary make next week specific recommendations to the future Commission President of better aligning the Commissioners portfolios to the competencies of the parliamentary committees? Will the two institutions try to follow a similar functional approach and make more visible and efficient the interrelation between the EP and the Commission? [6] It will be a good move as the dialogue between the Parliamentary committees and the Commissioners in several cases was not as direct as it should had been (see below).

Starting the new legislature on the right foot …

Hence the importance for the political groups at the beginning of this legislature to distribute their MEPs to the parliamentary committees responsible for the policies that are closest to their hearts or, paradoxically, that may create problems for them.

The composition of the committees in this legislature will be decided this week, and the following week (July 23) there will be constituent sittings and the election of presidential bureau of the Parliamentary Committees. In this regard, Parliament’s Rules of Procedure stipulate that it is up to the members of each committee appointing their chairpersons, but in order to facilitate the task and, above all, to prevent political groups with more members from taking the lion’s share, the political groups have agreed in advance to share out the chairmanships of the committees.

This was done following the so-called D’Hondt method, which, however, allowed the larger groups to choose the Commissions they considered most interesting for their political priorities.

Thus

– the EPP should have the chairmanship of the Committee on Foreign Affairs (AFET), Agriculture (AGRI), Fisheries (PECH), Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE), Constitutional Affairs (AFCO), Budgetary Control (CONT), and the subcommittee on Health (SANT);

– The Socialists have set the Economic and Monetary Commission (ECON), Environment, (ENVI), International Trade (INTA), Regional Development (REGI), and Women and Gender Equality (FEMM) as priorities;

– Patriots for Europe should have the Culture and Education (CULT) and Transportation and Tourism (TRAN) committees;

– the ECR Group should have the Budget (BUDG), Civil Liberties (LIBE) and Petitions (PETI) Committees;

– the Renew Group should have the Development (DEVE), Legal Affairs (JURI), and Security and Defense (SEDE) subcommittees;

– the Greens should have the Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO) Human Rights Subcommittee (DROI);

– the Left should have the Committee on Social Affairs and Labor (EMPL) the Committee on Taxation (FISC).

However, this indicative breakdown is in danger of being partially revised at the constituent meetings, either because the breakdown does not take into account the recent creation of a new political group to protect National Sovereignties or, above all, because the majority groups (EPP, SD and RENEW) have considered that missions of responsibility should not be entrusted to groups whose political agenda is to weaken the Union rather than to strengthen it.

The first sign of this came with the first controversy surrounding the plan to give the presidency of the Civil Liberties Commission (LIBE) to the Eurosceptic ECR group. This led to a pre-agreement between ECR and EPP to swap the presidencies of AGRI and LIBE with the LIBE Commission most likely going to a Spanish EPP MEP.

But the real problems may occur at the constituent meetings of the pre-attributed Commissions in addition to the ECR group, the “Patriots” group and the European Sovereigntists. In case the EPP-SD and RENEW majority wants to apply the so-called “cordon sanitaire” on the day of the constituent meeting there will be “majority” candidates who will be presented as an alternative of the “pre-attributed” ones and can be voted by the majority of the members of each committee to cover the first part of the legislature.

As has been tried to show in the lines above, the final choice will have certain consequences for the functioning of essential organs of the Parliament and of the Institution itself . (to be continued… )

[1] But is already mirroring also the Council position because after the trilogue and before the Plenary vote a letter is sent by the Council to the Parliament by which the Coreper announce that the Council will endorse the text as agreed during the trilogue. So that the text voted by the Plenary is already an interinstitutional agreement. Along the years this interinstitutional agreement has always been respected even when difficulties have emerged inside the Council after the conclusion of the trilogues (see the legislative procedures on the end of thermic motor and on nature restoration.

[2] According to the Council Rules of Procedure the Commission may intervene in the definition of the Council agenda, may ask for a vote to be taken, may be present in all the Council meetings also at Coreper and Council Working parties level….

[3] The European Parliament, the Council and the Commission: “Joint Declaration on Practical Arrangements for the Codecision Procedure of 13 June 2007” (Article 251 of the EC Treaty).

[4] Framework Agreement of 20 October 2010 on relations between the European Parliament and the European Commission (OJ L 304, 20.11.2010,

[5] Interinstitutional Agreement of 13 April 2016 between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission on Better Law-Making (OJ L 123, 12.5.2016, p. 1

[6] In the same perspective it would be sensible to reinstate in the EP Rules of procedures an old rule according to which the Commission should align its original proposal to the amendments adopted by the EP by so making easier the agreement with the Council (the latter should vote unanimously when the text does not mirror a Commission’s text.