14 October 2015 (NOTA BENE : This text is more than 60 pages)

by Douwe KORFF (FREE GROUP MEMBER)

About the Fundamental Rights Europe Expert Group (FREE): The Fundamental Rights European Experts Group (FREE Group : http://www.free-group.eu) is a Belgian non governmental organisation (Association Sans But Lucratif (ASBL) Registered at Belgian Moniteur: Number 304811. According to art 3 and 4 of its Statute ( see below *) the association focus is on monitoring, teaching and advocating in the European Union freedom security and justice related policies. In the same framework we follow also the EU actions in protecting and promoting EU values and fundamental rights in the Member States as required by the article 2, 6 and 7 of the Treaty on the European Union (risk of violation by a Member State of EU founding values)

About the author: Douwe Korff is a Dutch comparative and international law expert on human rights and data protection. He is Emeritus Professor of International Law, London Metropolitan University; Associate, Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford (Global Cybersecurity Capacity Centre); Fellow, Centre for Internet & Human Rights, University of Viadrina, Frankfurt/O and Berlin; and Visiting Fellow, Yale University (Information Society Project).

Acknowledgments: The author would like to express his thanks to Mme. Marie Georges and Prof. Steve Peers, members of FREE Group, for their very helpful comments on and edits of the draft of this Note.

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

We believe the following aspects of the Umbrella Agreement violate, or are likely to lead to violations of, the Treaties and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights:

- The Umbrella Agreement appears to allow the “sharing” of data sent by EU law enforcement agencies to US law enforcement agencies with US national security agencies (including the FBI and the US NSA) for use in the latter’s mass surveillance and data mining operations; as well as the “onward transfer” of such data to “third parties”, including national security agencies of yet other (“third”) countries, which the Agreement says may not be subjected to “generic data protection conditions”;

- The Umbrella Agreement does not contain a general human rights clause prohibiting the “sharing” or “onward transfers” of data on EU persons, provided subject to the Agreement, with or to other agencies, in the USA or elsewhere, in circumstances in which this could lead to serious human rights violations, including arbitrary arrest and detention, torture or even extrajudicial killings or “disappearances” of the data subjects (or others);

- The Umbrella Agreement does not provide for equal rights and remedies for EU- and US nationals in the USA; but worse, non-EU citizens living in EU Member States who are not nationals of the Member State concerned – such as Syrian refugees or Afghan or Eritrean asylum-seekers, or students from Africa or South America or China – and non-EU citizens who have flown to, from or through the EU and whose data may have been sent to the USA (in particular, under the EU-US PNR Agreement), are completely denied judicial redress in the USA under the Umbrella Agreement.

In addition:

- The Umbrella Agreement in many respects fails to meet important substantive requirements of EU data protection law;

- The Umbrella Agreement also fails to meet important requirements of EU data protection law in terms of data subject rights and data subjects’ access to real and effective remedies; and

- In terms of transparency and oversight, too, the Umbrella Agreement falls significantly short of fundamental European data protection and human rights requirements.

The Agreement should therefore, in our view, not be approved by the European Parliament in its present form.

FULL TEXT OF THE ANALYSIS

- Introduction / Background

In the wake of the revelations about massive global surveillance by the US National Security Agency (NSA) and the UK’s General Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the arrangements covering the transfers of personal data from the EU to the USA came under scrutiny. Serious doubts were raised about the adequacy of the (former) arrangements, including the European Commission’s “Safe Harbor” adequacy decision, the EU-US PNR Agreements, etc. – including about the arrangements (including Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties, MLATs) covering transfers of data from law enforcement agencies (LEAs) in the EU Member States and from EU judicial and police cooperation bodies such as Europol or Eurodac, to LEAs in the USA. One of the results of this scrutiny was the start of an EU-US dialogue on the adoption of a new agreement on the latter kinds of data exchanges. This new agreement was aimed at covering all the LEA data exchanges, under any of the special agreements: it would be an “Umbrella Agreement” that would not itself constitute a new legal basis for such data exchanges, but rather, would place the exchanges under the existing (and any future) data transfer agreements under a new overarching set of rules and principles, including in particular new forms of remedies for people whose data are protected under EU law (including the Charter).

The Umbrella Agreement

Following extensive political and technical discussions, at the 8-9 September 2015 EU-US Senior Officials meeting, the EU and the USA initialled the text of the EU-US Agreement on Data Protection in the cases of Exchanges of Personal Data for Law Enforcement Purposes, known as the “Umbrella Agreement” (hereafter referred to as such, or as “the Agreement”), attached as Attachment 1. EU Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality, Věra Jourová, informed the European Parliament of this in a letter to the Chair of the LIBE Committee, Claude Moraes, dated 14 September 2015.[1] The letter stressed that:

At this stage the text is still an internal document and I would appreciate it if you could, in accordance with the principle of loyal co-operation between the Institutions, treat it like that.

However, the text (and the letter) were quickly leaked and published on the website of the UK NGO Statewatch.[2]

As the letter explains, it is an essential prerequisite for the signature and conclusion of the Umbrella Agreement that the US Congress adopts the Judicial Redress Bill, put forward by the US Administration.[3] Ms. Jourová underlined the importance of a swift adoption of the Bill and urged MEPs to use their contacts in the US Congress to that end, adding:

Once the Bill is adopted, we will start the signature and conclusion procedure on the EU side in accordance with the Treaty. …

As far as the schedule of the next steps is concerned: first, the Council, on the basis of a proposal by the Commission, will have to adopt a decision authorising the signing of the Agreement. The Commission will make a proposal to the Council shortly after the adoption of the Bill. Subsequently, the decision on the conclusion of the Agreement requires the consent of the European Parliament.

This Note seeks to inform interested parties, and in particular MEPs, of the issues and questions that still arise in relation to the Agreement. It shows that, although the EU and US Justice and Home Affairs Senior Officials that initialled the Agreement expressed “extreme satisfaction” with it to each other,[4] the Agreement is in fact extremely weak and threatens to seriously undermine data protection for EU citizens and even more so for non-citizens in the EU (such as refugees and asylum seekers, or people flying to, from or through the EU), in the context of law enforcement EU-US data exchanges, in apparent breach of the Charter.

More specifically, as discussed at II.i, below, the Agreement, if approved, will do little or nothing to prevent further transfer of such – often highly sensitive – data to the US national security agencies, and/or to LEAs and NSAs of third countries.

- Core issues

Below, we address five broad sets of issues raised by the Umbrella Agreement. First of all, at II.i, we discuss the fact that the Agreement appears to allow for the “leaking” of data transferred subject to the Agreement, i.e., for the “sharing” of data transferred under the Umbrella Agreement to LEAs in a receiving state with the NSAs in that state, and for the “onward transfer” of such data to LEAs – and NSAs – in states that are not party to the Agreement (so-called “third states”). Next, at II.ii, we discuss a number of further general issues of fundamental importance to us Europeans, i.e.:

- the absence of a general human rights clause from the Agreement;

- the inclusion of certain dangerous legal presumptions in the Agreement; and

- issues of unequal treatment and discrimination – both between US “persons” and EU nationals and between EU nationals and other EU “persons”.

We believe that the defects identified in relation to these issues are likely to result in violations of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

After that, at II.iii, we provide assessments of the following more specific sets of issues, again from a European perspective:

- Whether the substantive standards set by the Agreement are adequate;

- Whether the rights and remedies offered to people whose data are transferred to the USA from the EU are adequate in scope, and “real and effective” in practice; and

- Whether the oversight regime provided for in the Agreement is adequate.

The issues discussed below are identified on the basis of an article-by-article analysis of the text of Agreement, contained in an Annex to this Note. Those detailed analyses also underpin the – often highly critical – views expressed below; and references to those analyses are therefore provided as appropriate. In section III, we set out our overall findings and recommendations.

II.i The “leaking” of data transferred subject to the Umbrella Agreement

The Umbrella Agreement is presented as essentially being (only) about data transfers between EU LEAs (such as Europol and Eurodac) and US LEAs, and the LEAs of the EU Member States (MSs) and US LEAs. However, closer reading of the Agreement shows that it envisages also further “sharing” of the transferred data with “other authorities”[5] including “authorities of constituent territorial entities of the Parties not covered by this Agreement”,[6] and “onward transfers” of the transferred data to “third parties”.[7]

Neither these “other authorities” nor these “third parties” are defined in the Agreement.

However, as the detailed analyses of the relevant articles in the Agreement in the Annex to this Note shows, the term “other authorities” appears to include the Parties’ national security agencies (NSAs), i.e., the EU’s security-related agencies,[8] the USA’s NSAs and effectively the EU Member States’ NSAs, at least to the extent that they can be said to be involved in “the prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of serious crimes” – which these days they increasingly are.[9] In the USA, this would certainly include the FBI, which now defines itself expressly as both an LEA and a NSA.[10] If and when the UK signs up to the Agreement,[11] it would certainly there include GCHQ, which is also increasingly officially involved in law enforcement matters, in particular in relation to serious organised crime and terrorism.[12] The same applies in other Member States.

The term “third parties” must be assumed to refer to (agencies of) “State[s] not bound by the [Umbrella] Agreement” and to other “international bod[ies]” – such as Interpol – as mentioned in Article 7.[13] As noted in the detailed analysis, the conditions for “onward transfer” of data to such entities are not as strict as might be assumed from a superficial reading of that article.[14]

In particular, the Umbrella Agreement forbids the EU or any EU MS from imposing “generic data protection restrictions” on the onward (internal-domestic) transfers or on third-party (third-state) disclosures of the data they have transferred to the USA subject to the Umbrella Agreement (Article 6(3)) – arguably in violation of the Treaties and the Charter and probably of the constitutions of at least some EU Member States (such as Germany), as discussed in section II.i, below, under the heading “dangerous legal presumptions”.

This means that the Umbrella Agreement must be seen in a wider context than just transatlantic law enforcement cooperation: it clearly links to:

- cooperation including data sharing between the LEAs of the EU and/or of the EU MSs, the security-related agencies of the EU,[15] and the NSAs of the MSs;

- cooperation and data sharing between LEAs of the USA and its NSAs (including the NSA);

- cooperation and data sharing between the NSAs of the EU MSs and those of the USA; and

- cooperation and data sharing between the NSAs of the EU MSs and those of the USA and the NSAs of other states (“third parties” in the terms of the Umbrella Agreement).

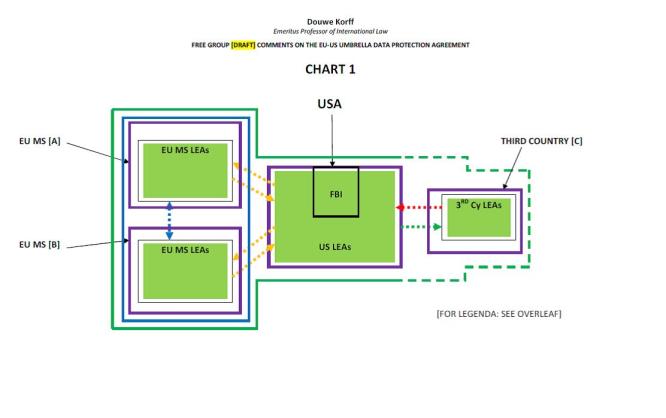

Attachment 3 to this Note contains two charts. The first (Chart 1) depicts the Umbrella Agreement as it is presented, i.e., in relation only to data transfers between EU LEAs and EU MS LEAs on the one hand, and the US LEAs on the other.

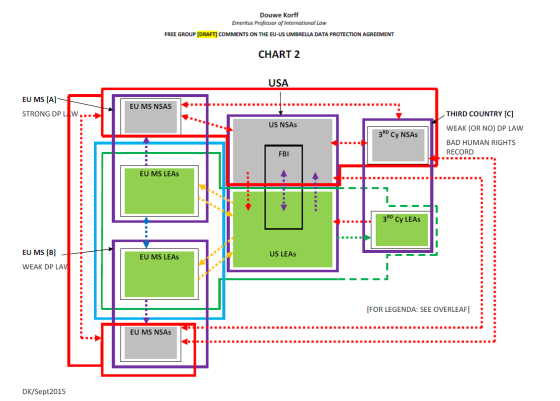

By contrast, Chart 2 shows the wider context as noted above, including the data sharing between LEAs and NSAs and between NSAs (in the EU, in the USA, and in other countries).

This is not the place to discuss the wider inter-state NSAs’ data-sharing arrangements and agreements in any detail. Suffice it to note that apart from the well-known “UKUSA” treaty that has grown into a treaty also involving Australia, Canada and New Zealand (the so-called “5EYES” club), there are many other “clubs” of countries sharing data between their NSAs with EU and/or US members, including:

- Brenner Club: Germany, the United Kingdom, France plus others;

- Club of Berne: EU Member States plus Norway & Switzerland;

- G6 Group: France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom;

- Lyon/Roma Group: G8 states;

- Megatonne: France and around 20-25 additional countries;

- Vienna Group: Austria, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland;

- Kilowatt Group: EU Member States, USA, Canada, Norway, Israel, Switzerland, and South Africa;

- Middle Europe Conference of Intelligence Services: Denmark, Bosnia and many others;

- Egmont Group: sixty-nine financial intelligence agencies;

- NATO Special Committee: Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, United Kingdom, United States, Greece, Turkey, Germany, Spain, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Albania, Croatia.

The USA (and probably also some – many? – EU Member States) also share data with further countries with which they have strategic alliances, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and Egypt (to name but a few).

The question of whether any of the data transferred from the EU to the USA subject to the Umbrella Agreement may lawfully be passed on under any of the cooperation and data sharing arrangements listed at (i) – (iv), above, is therefore far from a marginal issue – especially in the light of the very serious repercussions that can flow from the “onward transfer” of such data to NSAs in countries (such as some of those listed above) that have a bad human rights record.

Those consequences could be unacceptable even with regard to accurate data and/or valid assessments of the data subjects on the basis of the data (e.g., marking a person as “suspect” or “high risk” on a terrorist list), if they could expose the individual to arbitrary arrest and detention, an unfair trial, torture, “disappearance” or arbitrary, extrajudicial execution.

In addition, there could be similar consequences for totally innocent people if incorrect data or assessments of them, based on the data transferred subject to the Umbrella Agreement, were to be shared with such countries.

And of course, if the UK and the USA can more or less freely use the data disseminated under the Umbrella Agreement for their “national security” purposes, this means those data could quite simply be “hoovered up” into the massive global surveillance programmes exposed by Snowden – contrary to the clear wish of the European Parliament.

Yet all we can say about the legality of such onward transfers is that both general EU data protection law and the Umbrella Agreement are unclear in that respect.

Thus, the main current EU instrument on law enforcement data sharing, Council Framework Decision 2008/977/JHA,[16] expressly stipulates in Article 1(4) that it is:

without prejudice to essential national security interests and specific intelligence activities in the field of national security.

This clause may have been inserted to reflect the supposedly complete exemption of all “national security” matters from the competences of the Union[17] – but it still appears to introduce a serious loophole into the Framework Decision itself, especially when read together with the article on purpose-limitation (Article 3(2) of the Framework Decision):

Further processing for another purpose shall be permitted in so far as:

- it is not incompatible with the purposes for which the data were collected;

- the competent authorities are authorised to process such data for such other purpose in accordance with the applicable legal provisions; and

- processing is necessary and proportionate to that other purpose.

Thus, as long as the protection of the “national security” interests of the relevant MS is regarded as “not incompatible” with the law enforcement purposes for which the data were obtained, and provided that the domestic law of the MS in question allows the disclosure, the Framework Decision appears to permit the disclosure of any data transferred to the MS from another MS (or from an EU LEA body) under the Framework Decision to the receiving MS’s NSA – and what that MS’s NSA then does with those data (including whether it shares it further with the NSAs of other countries, within or without the EU), is apparently not a matter that EU law concerns itself with at all.[18]

The Framework Decision is soon (?) to be replaced by a Law Enforcement Data Protection Directive, currently in the EU legislative process. Until the final text of this LEDP Directive is agreed, EU law on the “leaking” of law enforcement data to NSAs (in the EU, in the USA, and beyond) will remain unclear.

We believe that the above calls, first of all, for the insertion of a general data protection clause in the Umbrella Agreement, as proposed in section II.ii, below (indeed, such a clause should be included in any international agreement to which the EU is a party that impacts on fundamental rights). In addition, we believe that the European Parliament, when considering the Umbrella Agreement, should squarely address this “leaking” of data to NSAs, including to the US NSA and the UK GCHQ, for use in their world-wide surveillance programmes, and reject the Agreement unless additional, clear, strict and binding undertakings are obtained to fully protect EU data subjects in this regard.

II.ii General, fundamental issues

The absence of a general human rights clause from the Agreement

Personal data are dangerous, especially when processed in a context – i.e., law enforcement and anti-terrorist/national security measures – in which they can inherently be the basis for measures that seriously impact on the data subjects’ rights and freedoms. Seemingly incriminating but factually erroneous information, or wrongful assessments of individuals – e.g., as “suspect” or “high risk” on an anti-terrorist list – can lead to repressive action by LEAs (and NSAs, when they have executive/enforcement powers, as in the USA, and when the data can be shared with them, as is often allowed both in the EU and the USA), ranging from being wrongly placed on a “no-fly” list, through unwarranted arrest, detention and interrogation, to imprisonment – or worse.

It is bad enough if such errors occur in states that (more or less) adhere to the Rule of Law, such as the parties to the Umbrella Agreement – although in the context of the fight against terrorism, they too have at times seriously betrayed that commitment. But if the factually erroneous data – or even incomplete or ambiguous data – and/or such assessments are passed on (“further forwarded”) to LEAs (and NSAs) of countries that do not respect the Rule of Law – that use arbitrary arrest and detention, “disappearances” and torture – then those that pass on the data become complicit in such abuses.

We feel that there therefore ought to be, in any relevant treaty but certainly also in the Umbrella Agreement, a general human rights clause that prohibits cooperation with third-party states’ LEAs – and NSAs – in any circumstances in which this can lead to such serious human rights violations. More specifically, in relation to any agreement on the processing and further forwarding of personal data, including the Umbrella Agreement, there should be a clause prohibiting the passing on of any data covered by the agreement in circumstances in which such further transfers can lead to such violations.

We urge the European Parliament not to approve the Umbrella Agreement until and unless a general human rights clause has been added to it.

But in any case, in the absence of such a clause, any provisions on the further transfer of the data from any of the parties – i.e., the EU, EU Member States, and the USA – to any third country, should be most rigorously assessed to see if they expressly or by implication allow for sharing or forward transfers of data that could lead to serious human rights violations; and any provisions that could be read as allowing this should be amended so as to clearly prevent it.

Dangerous legal presumptions

Article 5(3) of the Agreement stipulates that, once the parties have taken “all necessary measures to implement [the Umbrella Agreement]”:

the processing of personal information by the United States, or the European Union and its Member States, with respect to matters falling within the scope of this Agreement, shall be deemed to comply with their respective data protection legislation restricting or conditioning international transfers of personal information, and no further authorization under such legislation shall be required.

Thus, once the USA has implemented the Agreement, its processing of any data transferred to it subject to the Agreement – including data transferred to it under the EU-US MLAT, any US-EU MS MLAT, the EU-US PNR Agreement, etc. – must be “deemed to comply” with EU data protection law, presumably even including the Charter.

In addition, Article 6(3) stipulates that when data are transferred in a specific case (i.e., under an MLAT, as distinct from agreements covering bulk transfers of data unrelated to a specific case, such as bulk PNR data), the transferring LEA may impose “additional conditions” on the use of the data – but then adds that:

Such conditions shall not include generic data protection conditions, that is, conditions imposed that are unrelated to the specific facts of the case.

(As explained in the analysis of Article 9 of the Agreement in the Annex to this Note, this provision reflects Article 9 of the EU-US MLAT, as interpreted in the Explanatory Note on that Agreement.)

Similarly, Article 7(4) stipulates that while “requirement[s], obligation[s] or practice[s]” pursuant to which the consent of the transferring authority or State is required before data transferred subject to the Umbrella Agreement are “further transferred” to “[another] State or body bound by [the Umbrella Agreement” are not affected by the Agreement, in fact it adds the proviso to this that:

the level of data protection in such State or body shall not be the basis for denying consent for, or imposing conditions on, such transfers.

In other words, parties to the Umbrella Agreement are no longer allowed to rely on such prior consent stipulations in such other treaties to prevent an onward transfer to “another body bound by [the Umbrella Agreement]”, merely because it believes that the level of data protection in the country of the final recipient (and more specifically, the level of data protection as applied to the end-receiver of the data), is not sufficient.

As noted at II.i, those end-receivers may well be the NSAs of the country to which the data were transferred.

All these provisions clearly appear to try to bar the EU and the EU Member States, and indeed the CJEU and any EU Member State constitutional court, from prohibiting transfers – also of data on its own citizens or residents – or from imposing “generic” conditions on transfers, on the basis that the end-receiver of the data is not effectively subject to an appropriate level of data protection.

Since such prohibitions or “generic conditions” might well flow from the Charter (in relation to the EU and EU institutions), or from a Member State’s constitutional requirements, this prohibition can again raise serious issues in relation to EU and Member States’ domestic constitutional law.

It would appear, for instance, that an EU MS may not impose the “generic condition” for transfers involving or including data on non-nationals of that MS (such as refugees settled in that state but not granted citizenship), that those data should be protected equally as are data on the Member State’s nationals (cf. the next sub-section, on “Unequal treatment and discrimination”). But transferring the data to the USA without such a condition – i.e., allowing discrimination in this regard, by the US receiving authorities, between [data on] the MS’s nationals and residents that are not citizens – may well be in violation of the Member State’s constitution, or the EU Charter.

Unequal treatment and discrimination

Article 4 of the Umbrella Agreement stipulates that:

Each Party shall comply with its obligations under this Agreement for the purpose of protecting personal information of its own nationals and the other Party’s nationals regardless of their nationality, and without arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination.

As noted in the Annex to this Note, this article emphatically does not say that each party shall provide equal protection of any personal data processed by its LEAs relating to, on the one hand, its own nationals, and on the other, the nationals of the other party. First of all, the obligation to treat nationals of the EU (= EU citizens) and US nationals the same only applies in relation to “[the parties’] obligations under this Agreement”. In respect of anything that is not covered by the agreement, the parties can make (or retain) as many distinctions as they like.

Secondly, the principle of equality only applies to nationals of the EU and the USA. Data on (say) an Australian or Afghan resident in the EU, or flying to or from the EU (PNR!) – or on, say, any Syrian refugees given asylum in the EU but not citizenship – would not appear to be equally protected. At most, they (and their data) should not be subjected to “arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination” – which is a rather different test from equal treatment

This unequal treatment and discrimination is carried through to, and further reinforced, in particular in connection with judicial redress against violations of the Agreement – which under Article 19 of the Umbrella Agreement is expressly limited to citizens of the parties (the USA, the EU and the EU Member States).

Thus, as noted in the analysis of Article 19 in the Annex, non-EU citizens living in EU Member States who are not nationals of the Member State concerned – such as Syrian refugees or Afghan or Eritrean asylum-seekers, or students from Africa or South America or China – and non-EU citizens who have flown to, from or through the EU and whose data may have been sent to the USA (in particular, under the EU-US PNR Agreement), are all completely denied judicial redress in the USA under the Umbrella Agreement.

In fact, ironically, until and unless Denmark, the UK and Ireland join the Umbrella Agreement, their own citizens are also completely denied such judicial redress in the USA because the Agreement – and thus also Article 19 – does not cover them until that happens (Article 27).

This stands in direct contrast to the fundamental position laid down in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, reflecting the core principle of universality of human rights in all the main international and European human rights treaties, that the “right of an effective remedy”, including a judicial remedy should be accorded to “everyone” (Article 47(1)), “[without] discrimination” (Article 21(1)), and (except for special cases provided for in the EU Treaties that are not relevant here) “[without] any discrimination on grounds of nationality” (Article 21(2). The recent CJEU judgments in M and S and Weltimmo confirmed that EU data protection law applied regardless of (EU) nationality.

The general distinction made between nationals of the parties and non-nationals in Article 4 of the Agreement, and the even worse distinction between citizens and non-citizens of the parties in Article 19 are, in our view, in clear breach of the Charter (and European and international human rights- and data protection law).

II.ii Whether the substantive standards set by the Umbrella Agreement are adequate

In the Annex to this Note, the various substantive provisions of the Umbrella Agreement are analysed in some detail. Here, it must suffice to summarise those issues with regard to which the standards set out in the Agreement appear to fall significantly below the basic EU (and wider European) standards. These include the following:

- Certain activities, which in EU data protection law are expressly regarded as falling within the definition of “processing” are not included in the definition of that term in Article 2(2) of the Agreement, i.e.: “recording”, “storage”, “retrieval”, “consultation”, “otherwise making available [of data]”, “alignment or combination”; “blocking”. The omission of “alignment or combination” – i.e., of “data matching” – is significant in particular in relation to “profiling”: see below.

- The provision covering “further processing” of transferred data for purposes that are “not incompatible” with the purpose for which the data were transferred (Article 6) could be read as allowing such “further processing” for the purposes of essentially any “international agreement” entered into “for the prevention [etc.] of serious crimes.” That would seem to be very open-ended – especially in view of the reference to authorities other than law enforcement ones (i.e., which can include national security agencies). As we conclude in our analysis of this article (with reference also to the lack of clarity over who can be regarded as a “Competent Authority” in terms of the Agreement: see the analysis of Article 3(2)):

It will be important to clarify that neither data disclosures allowed under the terms of treaties between EU Member States and the USA on national security cooperation, nor the (further) disclosure of the data within the USA to the US national security authorities are to be deemed to be “compatible” (“not incompatible”) with the Umbrella Agreement, simply because they are done “pursuant to the terms of existing international agreements”. This should apply a fortiori to any secret (or partially secret) treaties of such a kind – which by their very nature do not constitute “law” in the sense of the Charter and can therefore never be a basis for any interference with fundamental rights.

- Article 6(5) stipulates that personal data provided in bulk, such as PNR data, must be processed in a “manner” that is “directly relevant to and not excessive or overbroad in relation to the purposes of such processing” – but this not the same as the data themselves having to be “directly relevant to and not excessive or overbroad in relation to the purposes of such processing”, as is required under EU data protection law. Since much of the data contained in PNRs are (i) “irrelevant and excessive” for normal law enforcement purposes, and (ii) are used for profiling purposes,[19] one may wonder if this odd text is an attempt to allow for the transfer of “irrelevant, excessive and overbroad” data, as long as they are not used in an “irrelevant, excessive and overbroad” manner? (With the US authorities of course arguing that their data analyses and profiling operations are not “irrelevant, excessive and overbroad”.)

- Article 7(1) allows a transferring authority to “consent” to the further transfer of data transferred in connection to specific cases (i.e., under MLATs; not bulk data) to states and agencies not bound by the Agreement. Not only is this left entirely in the hands of the transferring authority, without a need to even consult the relevant data protection authority, Article 7(2) also suggests that in considering whether to give such consent, data protection concerns and requirements can be “traded off” against the importance of making the data available to the state or authority not bound by the Agreement. As we conclude in our analysis of this provision in the Annex:

The “trading off” of data protection against the interests of international LEA cooperation is dangerous. At the very least, this requires a much more detailed set of provisions. And again, these matters should not be left to the sending LEA to weigh, but should be in the hands of the relevant (i.e., LEA sector-specific) DPA. There should also be full transparency about the way this provision is applied in practice: see the analysis of Article 20, below.

- Article 7(3) allows the further transfer of data unrelated to specific cases, such as PNR data provided in bulk under the EU-US PNR Agreement, subject to the conditions in the relevant agreement, without adding further safeguards save only that there should be “appropriate information mechanisms between the Competent Authorities”. As we conclude in the analysis of this provision in the Annex:

If [such onward transfers of bulk data] are allowed, they should be very strictly regulated – we are talking here of massive amounts of data on mostly totally innocent individuals, yet which can be clearly used against them by repressive governments (e.g., if they show travel to certain events, or contacts with certain people or groups).

Just having “appropriate information mechanisms between the Competent Authorities” is not nearly enough. Again, at the very least, this requires a much more detailed set of provisions. Again, these matters should not be left to the sending LEA to weigh, but should be in the hands of the relevant (i.e., LEA sector-specific) DPA. And again, there should be full transparency about the way this provision is applied in practice: see my comments on Article 20, below.

- Article 8 sets out the “data quality” requirements for data transferred under the Umbrella Agreement – but in terms that fall considerably short of the European standards. Specifically, the provision contains weasel-words that significantly tone down the requirements of the provision: the states concerned must take “reasonable steps” (not even: “all reasonable steps”) to ensure “such accuracy”, etc., as is necessary and “appropriate”; and they need only inform each other of “significant doubts” about such matters, and even then only “where feasible”. By contrast, EU data protection law stipulates that the controller is under a legal obligation to “ensure” that the data are adequate, relevant, not excessive, accurate and up to date. Moreover, Article 8 omits to spell out what remedial action must be taken if data are identified as (actually or possibly) inaccurate, irrelevant, out of date, or so incomplete as to be potentially misleading. This is a serious omission, because the USA takes the position (expressly, in a binding Explanatory Note to the EU-US MLAT) that in respect of inaccurate or incorrect or even improperly or unlawfully processed data, measures “other than the process of deletion” can be sufficient “to protect the privacy or the accuracy of the personal data”. The provisions on rights of data subjects and remedies, discussed below at II.iii and II.iv, if anything reinforce the view that deletion or erasure of such data can be avoided by the USA in circumstance in which, in the EU, that would be required.

- Contrary to EU data protection law, the provision in the Umbrella Agreement on data security (Article 9) does not require the USA to protect data transferred to it under the Agreement against “all … unlawful forms of processing”; rather, it only refers to protection against “accidental or unlawful destruction”, “accidental loss” and “unauthorized disclosure, alteration, access, or other processing”.

- Articles 10 and 11 addresses data security breaches and data breach notification. We refer to our analyses of these articles in the Annex for details. Suffice it to note here that we conclude on the basis of that analysis as follows:

In simple terms: Article 10 in its current form is so full of limitations, qualifications and caveats that it totally fails to ensure serious transparency about data breaches compromising personal data (including highly sensitive personal data) on EU persons by US authorities. Whenever the US authorities would feel reluctant to inform EU authorities of data breaches relating to (or including) data sent to the US LEAs by any EU- or EU Member State LEA, they could easily find a reason to avoid doing so – and keep the data breach secret. And even when they did inform the relevant EU- or EU Member States’ LEAs, they could prohibit those latter (European) LEAs from passing on the information on the data breach to their data protection oversight bodies.

- Especially in relation to highly sensitive processing of often highly sensitive data by law enforcement authorities, scrupulous record-keeping and the keeping of tamper-proof logs is essential to allow for effective oversight. However, as our analysis of the relevant provision in the Umbrella Agreement (Article 11) shows, the requirements in this respect are again insufficient. In particular, Article 11 does not spell out that the records and logs must cover all the matters subject to the Agreement; that they should be tamper-proof (or at least that any tampering must be discernible); or – crucially – that the oversight bodies should have full and complete and unhindered access to the records and logs in question, both in relation to their own national oversight and in relation to joint oversight missions. As we conclude in our analysis in the Annex: Without such clear stipulations, the Agreement again fails to ensure real, i.e., verifiable, compliance with the requirements of data protection laws and principles.

- Data retention is addressed in Article 12 of the Agreement. We may again refer to our detailed analysis of that article in the Annex, and limit ourselves to quoting from our conclusions in this respect, i.e. that:

As it stands, the text of Article 12 does not appear to ensure that personal data transferred by European LEAs to their US counterparts in relation to specific cases, investigations or prosecutions are not retained by the US authorities for longer than is necessary for those cases, investigations or prosecutions.

In relation to untargeted, suspicion-less bulk data provided by European LEAs to the US LEAs under separate agreements (such as the EU-US PNR Agreement), Article 12(2) stipulates that any such separate agreement must include “a specific and mutually agreed-upon provision on retention periods”. Full analysis will therefore depend on what such other treaties stipulate in this regard.

However, given the serious, fundamental problems with compulsory, suspicion-less collection and retention of bulk data in the EU legal order, and in many EU Member States’ legal orders, the stipulation in the Umbrella Agreement is in this respect much too lackadaisical … does not in any way ensure compliance with the [CJEU’s] data retention judgment.

- Article 13(1) of the Agreement lists essentially the same categories of data as “special” (or “sensitive”) as Article 8(1) of the 1995 Data Protection Directive. However, it does not reflect the further developments in this respect, as reflected in the text of the General Data Protection Regulation. Thus, the Umbrella Agreement does not expressly mention “genetic data” and “biometric data”, “gender identity” or “trade union activities” as sensitive data. It also, unlike the GDPR, does not clarify (as the Commission and Parliament want to do in the Regulation) that information which “relates to … the provision of health services to the individual” as “health data” and thus sensitive. In the USA, such data is generally treated under the “third party” rule as not just not sensitive but essentially freely tradeable. We conclude that:

It is therefore clear that the Agreement does not treat all the data that are already regarded as sensitive in EU data protection law, or that will soon be explicitly so regarded, as sensitive. This is extremely likely to lead to processing by receiving US LEAs of the data contrary to EU law –

and go on to show that this view is reinforced by the weak reference in the first sentence of Article 13(1) to “appropriate safeguards in accordance with law”, which are not adequately clarified but clearly need not in all cases require the measures listed in the article; and which are to be applied (with regard to sensitive data transferred to the USA from the EU) in accordance with the in this respect extremely weak US legal standards.

Article 13 also clearly falls short of the rule on the processing of sensitive data by law enforcement bodies, set out in the COE guidelines on such processing, Recommendation R(87)15 (Point 2.4).

On the contrary: Article 13(2) expressly envisages the transfer of “such data” – i.e., of sensitive personal data – under other agreements “other than in relation to specific cases, investigations or prosecutions”. Rather than prohibiting such transfers for untargeted data collecting and -mining, as should be done under Recommendation R(87)15, it says that such (other) agreements should “further specify the standards and conditions under which such information can be processed, duly taking into account the nature of the information and the purpose for which it is used.” That is direct conflict with the (in the EU: effectively binding) Recommendation.

As further noted in relation to Article 15 on “automated decision-making”, below, there is also nothing in the Agreement on the use of sensitive data in profiling generally, or to counter the risk that this may result in discrimination in particular. Given the serious concerns about profiling, this too is an egregious omission.

- The “mining” of bulk data and the creation of “profiles” on the basis of such data mining poses serious threats to the fundamental rights of those to whom the profiles are applied, a fortiori if the data mining and profiling is done in a law enforcement- or anti-terrorist/national security context, especially if the aim is to “identify” people who may be terrorists or serious criminals.[20] Unfortunately, the Umbrella Agreement does anything to prevent such dangerous profiling. Article 15 in principle envisages “human involvement” in any automated decision-making. However, in a law enforcement/anti-terrorist context, it is extremely unlikely that the “human involvement” will include any opportunity on the part of the person affected by the decision (e.g., a person who is labelled “high risk” on an anti-terrorist database) to argue against the decision, or the ranking, or to put forward facts or arguments against them. Indeed (as noted in the analysis of Article 16 in the Annex), unlike under the EU instruments, under the Umbrella Agreement data subjects are not even entitled to basic information on the “logic” used in automated decisions that affect them. The effectiveness of the “human involvement” requirement of Article 15 must therefore be regarded as inherently largely meaningless.

Worse, in direct contrast to the view of the European Parliament, Article 15 of the Umbrella Agreement expressly allows the taking of fully automated decisions (i.e., typically, of decisions based on profiles) without any human intervention, provided only that there are “appropriate safeguards”, but which are not spelled out other than that they must include the possibility of human intervention. Under the Umbrella Agreement, actual human intervention in all cases is therefore clearly not necessary in all cases of automated decision-making/the taking of decisions on the basis of profiles. As we conclude in our analysis in the Annex:

It would be odd indeed if the EU, following the Parliament proposal, were to prohibit the taking of significant decisions on the basis of profiles without human intervention in the EU, but would (by ratifying the Umbrella Agreement) allow US LEAs – and indeed the NSA – to take such decisions without human intervention, in respect also of people living in the EU (be they EU citizens or asylum seekers or refugees).

Moreover, as already noted above, there is also nothing in the Agreement – and in Article 15 in particular – on the use of sensitive data in profiling generally, or to counter the risk that this may result in discrimination in particular. This is in stark contrast to the rules on profiling in the Draft General Data Protection Regulation.

It should be clear from the above that the Umbrella Agreement in many respects fails to meet important substantive requirements of EU data protection law.

II.iii Whether the rights and remedies offered to people whose data are transferred to the USA from the EU are adequate in scope, and “real and effective” in practice.

The articles dealing with the rights and remedies offered to data subjects under the Umbrella Agreement are again analysed in some detail in the Annex. Here, we therefore again limit ourselves to summaries of our main findings in those respects. These include the following:

- On the right of data subject to obtain access to their data, we refer to our quite extensive analysis of Article 16 of the Agreement, in the Annex. Here, it must suffice to note, first of all, that the Agreement says nothing about the “quality” of any US law restricting subject access, thereby allowing for restrictions on access in the USA on the basis of vaguely-worded provisions in US laws that are not “foreseeable” in their application. The text of the Agreement would in fact not even appear to prohibit restrictions on access, based on secret laws or secret interpretations of the US laws (such as have bedevilled the legal regime relating to NSA surveillance).

Secondly, in the USA, subject access can be denied when this is “reasonable” to protect law enforcement activities, while in Europe, the denial must be “indispensable” to that end – a very significant difference.

There is a further matter of importance. Article 16(4) stipulates that individuals can authorise an “oversight body” – in the EU, a Data Protection Authority (DPA) – to request access on his or her behalf. This is also provided for in many European systems with regard to access to LEA data. However, unlike the European systems, under the Umbrella Agreement, such a designated DPA is not entitled to full access to the data (while being limited in what it can disclose to the data subjects about its findings). Under the Umbrella Agreement, a thus-designated European DPA would, as far as subject access is concerned, be essentially in the same position as anyone else who might be authorised by the data subject to act on the latter’s behalf (e.g., a European, or indeed a US NGO): the DPA (or the NGO) does not have any right of further access than the data subject him- or herself. If a European data subject is denied access to his or her data held by a US LEA, or granted only limited access, any European DPA acting on the data subject’s behalf would be subject to those very same restrictions.

Moreover, as noted in the analyses of Articles 18 and 21, below, the relevant “oversight bodies” in the USA are also not granted the kind of full access given to LEA data in the above-mentioned EU systems.

Enforcement of subject access is therefore, under the Agreement, also much weaker in the USA than in the EU.

Similar issues arise in respect of the right to rectification under Article 17 of the Agreement. Thus, the latter right is also to be granted in the way, and to the extent, that this is provided for in the US legal framework, which, as we have noted, in particular does not require that the right is laid down in clear and precise, published law that is foreseeable in its application. Furthermore, although a European data subject can again authorise the relevant (possibly LEA-specific) DPA of his or her own Member State – or, in respect of data sent to the USA by a EU law enforcement institution, the EDPS – to act on his or her behalf (Article 17(3)), the latter can again not act as a DPA would be able to do in many EU Member States, and get full access to the data (while being restricted in what can be disclosed to the data subject). Rather, the European DPA would not be allowed to check for itself whether, in its view, the data need “correcting” or “rectifying” (as further discussed below). Rather, the determination of whether any data that are being challenged as being inaccurate or as having been “improperly processed” is again left to the US LEA in question.

Moreover, again, as noted in the analyses of Articles 18 and 21, below, the relevant “oversight bodies” in the USA are also not granted the kind of full access given to LEA data in the above-mentioned EU systems.

Like enforcement of subject access, enforcement of the right to rectification is therefore, under the Agreement, also much weaker in the USA than in the EU.

But there is a further important defect under the Agreement in this respect – which is that unlike under EU data protection law, the Agreement does not mention “deletion” or “erasure” of data as required in certain circumstances, such as when the data have been unlawfully obtained or further processed. In the light of the Explanatory Note to the EU-US MLAT, already mentioned, this strongly suggests that the US authorities are determined to avoid any formal legal requirements, under the Umbrella Agreement or under EU-US MLAT of 2003, to ever fully delete data, even if the data were shown to be inaccurate and/or processed in violation of the Agreement (or the MLAT); and even more so, any formal requirement to inform third parties to whom the inaccurate or improperly processed data were transferred, of such a need for deletion.

The Umbrella Agreement (and for that matter, the EU-US MLAT of 2003) thus also falls clearly short of the normal, basic EU data protection rules and principles in respect of the right to correction or deletion of inaccurate or improperly processed data.

- On the question of “administrative redress” (Article 18 of the Agreement), it may suffice to note that (although for once accorded to “any individual” rather than to EU and US nationals or –citizens only), it is limited in scope and amounts to nothing more than an entirely internal self-policing review of its actions by the authority to whom a complaint is made. In particular, there is no provision for the involvement of the relevant “oversight body” – or rather, in the USA, bodies – in the review; and any EU DPA that may have been appointed by the data subject is not granted any special status in the processing of the complaint: the DPA is, in particular, not granted any right of access to any relevant data that are not already available to the data subject (see further below, at II.iv, on the question of oversight). As we conclude in our analysis:

It is therefore difficult to see how the “administrative redress” provided for in Article 18 can be of any real value.

- The article on “judicial redress” (Article 18) and the Judicial Redress Bill to which it refers (without expressly naming it) has been hailed as the greatest achievement of the Umbrella Agreement. It therefore deserves particularly close attention and analysis. Unfortunately, once again, such an analysis shows that it does not live up to what it seems to promise. There are two elements to this. First of all, as already discussed at II.i, above, the provision expressly discriminates against non-citizens and completely denies judicial redress to data subjects from the EU who are not nationals of citizens of an EU Member State, such as refugees and asylum-seekers, and non-EU/non-US travellers whose data has been passed on to the USA under the EU-US PNR Agreement or other agreements. This is clearly and manifestly in direct violation of the Charter and of international and European human rights law.

In addition, as shown in some detail in the analysis in the Annex, judicial redress for EU citizens is far too limited. In particular, it would appear that they cannot obtain a judicial order for the deletion or erasure of inaccurate or improperly (indeed, even unlawfully) processed data; and they cannot obtain compensation for damages caused by the information being incorrect, or improperly processed by the US agency. They can only obtain compensation if they can prove actual damages arising from wilfully and intentionally unlawful disclosures of their data by the receiving US agency. This falls far short of an appropriate judicial redress system, such as must be available to “everyone” under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Clearly, the Umbrella Agreement thus also fails to meet important requirements of EU data protection law in terms of data subject rights and data subjects’ access to real and effective remedies.

II.iv Whether the oversight regime provided for in the Umbrella Agreement is adequate

Finally, we summarise below our most important findings in terms of oversight over the application of the Umbrella Agreement and the actions of the relevant “Competent Authorities”.

- In that respect, we found first of all that in respect of “transparency” – which is a sine qua non for effective oversight and accountability – the relevant provision (Article 20) provides for the general making available of much less information than European controllers are required to make public (directly or indirectly, through DPA registers of notified processing details). More importantly, Article 20 of the Umbrella Agreement appears to allow US domestic law to stipulate that any of the matters listed in Article 20(1) shall not be made public, as long as such a restriction on transparency is “reasonable” in US-domestic-legal terms. Given the sweeping exceptions and exemptions from the normal rules, already provided for in US law for the benefit of “national security” – which is itself excessively widely defined in US law – and for “protecting law enforcement-sensitive information”, Article 20(2) appears to be little less than a carte blanche for the US legislative authorities to effectively nullify the transparency seemingly provided for by the first paragraph.

- As concerns oversight itself, we must refer to the detailed analysis of Article 21 in the Annex, with reference in particular to the strengthening of European law in that regard under the Charter of Fundamental Rights, the Additional Protocol to the Council of Europe Data Protection Convention and the soon-to-be-adopted General Data Protection Regulation. Here, we should highlight that under the Umbrella Agreement oversight in the USA can be disbursed between a range of unspecified different “officers”, “offices”, “oversight boards” and “other bodies”, all with different briefs, competences and powers.

Within the still limited scope of the Annex, it was impossible to analyse all the possible officers, offices, boards, etc.. The Umbrella Agreement does not even list them. However, it was is clear is that there are, in the USA, no single bodies that combine in themselves the requirements of independence and powers of investigation and intervention that are seen as key to the adequacy of European supervisory authorities. Some do not have jurisdiction in respect of much of the processing. Some may have the right to raise questions, perhaps also on behalf of data subjects – but without being given the right to investigate independently, with full access to all the relevant data (even if not all may be revealed to the complaining data subjects). Some may be able to make recommendations in respect of corrections or additions or other “remedial actions” – but as far as we know, none can order such changes. What is more, as discussed in the analyses of Articles 17 and 18 in the Annex, US law and practice generally appears to never consider compulsory deletion of data – even of data proven to be incorrect or improperly, or even unlawfully, processed – to be mandatory; and none of the US officers, bodies, etc., that could possible be regarded as falling within the list in Article 21(3) will, as far as we can see, ever be able to order it. We therefore concluded that:

In our view, the oversight offered in this article on the US side falls far short of the minimum European requirements for “independent [supervisory] authorities”, enshrined in the Additional Protocol to the COE Data Protection Convention or, what is more, in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Given that in, Europe, oversight by such truly independent and fully empowered authorities is seen as crucial to adequate protection and as constitutionally required, the absence of serious guarantees to that effect in the Umbrella Agreement again raise serious doubts about its validity in terms of the Charter and EU law.

In terms of transparency and overight, too, the Umbrella Agreement falls significantly short of fundamental European data protection- and human rights requirements.

- Overall conclusions

We believe the following aspects of the Umbrella Agreement violate, or are likely to lead to violations of, the Treaties and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights:

- The Umbrella Agreement appears to allow the “sharing” of data sent by EU law enforcement agencies to US law enforcement agencies with US national security agencies (including the FBI and the US NSA) for use in the latter’s mass surveillance and data mining operations; as well as the “onward transfer” of such data to “third parties”, including national security agencies of yet other (“third”) countries, which the Agreement says may not be subjected to “generic data protection conditions”;

- The Umbrella Agreement does not contain a general human rights clause prohibiting the “sharing” or “onward transfers” of data on EU persons, provided subject to the Agreement, with or to other agencies, in the USA or elsewhere, in circumstances in which this could lead to serious human rights violations, including arbitrary arrest and detention, torture or even extrajudicial killings or “disappearances” of the data subjects;

- The Umbrella Agreement does not provide for equal rights and remedies for EU- and US nationals in the USA; but worse, non-EU people living in EU Member States who are not nationals of the Member State concerned – such as Syrian refugees or Afghanistani or Eritrean asylum-seekers, or students from Africa or South America or China – and non-EU people who have flown to, from or through the EU and whose data may have been sent to the USA (in particular, under the EU-US PNR Agreement), are completely denied judicial redress in the USA under the Umbrella Agreement.

In addition:

- The Umbrella Agreement in many respects fails to meet important substantive requirements of EU data protection law;

- The Umbrella Agreement also fails to meet important requirements of EU data protection law in terms of data subject rights and data subjects’ access to real and effective remedies; and

- In terms of transparency and overight, too, the Umbrella Agreement falls significantly short of fundamental European data protection- and human rights requirements.

The Agreement should therefore, in our view, not be approved by the European Parliament in its present form.

– o – O – o –

Drafted on behalf of the FREE Group by Douwe Korff

Cambridge, September-October 2015

Attached:

Attachment 1: EU-US Agreement on Data Protection in the cases of Exchanges of Personal Data for Law Enforcement Purposes (the “Umbrella Agreement”).

Attachment 2: Letter EU Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality, Věra Jourová, informed of this in a letter to the Chair of the LIBE Committee of the European Parliament, Claude Moraes, dated 14 September 2014.

Attachment 3: Two Charts accompanying section II.i of this Note.

Annex: Article-by-article analysis of the EU-US Umbrella Data Protection Agreement.

ATTACHMENT 1

(Draft for initialling)

AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION ON THE PROTECTION OF PERSONAL INFORMATION RELATING TO THE PREVENTION, INVESTIGATION, DETECTION, AND PROSECUTION OF CRIMINAL OFFENSES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preamble

Article 1: Purpose

Article 2: Definitions

Article 3: Scope

Article 4: Non-discrimination

Article 5: Effect of the Agreement

Article 6: Purpose and Use Limitations

Article 7: Onward Transfer

Article 8: Maintaining the Quality and Integrity of Information

Article 9: Information Security

Article 10: Notification of an Information Security Incident

Article 11; Maintaining Records

Article 12: Retention Period

Article 13: Special Categories of Personal Information

Article 14: Accountability

Article 15: Automated Decisions

Article 16: Access

Article 17: Rectification

Article 18: Administrative Redress

Article 19: Judicial Redress

Article 20: Transparency

Article 21: Effective Oversight

Article 22: Cooperation between Oversight Authorities

Article 23: Joint Review

Article 24: Notification

Article 25: Consultation

Article 26 : Suspension

Article 27: Territorial Application

Article 28: Duration

Article 29: Entry into force and Termination

TEXT OF THE AGREEMENT

Mindful that the United States and the European Union are committed to ensuring a high level of protection of personal information exchanged in the context of the prevention, investigation, detection, and prosecution of criminal offenses, including terrorism;

Intending to establish a lasting legal framework to facilitate the exchange of information, which is critical to prevent, investigate, detect and prosecute criminal offenses, including terrorism, as a means of protecting their respective democratic societies and common values;

Intending, in particular, to provide standards of protection for exchanges of personal information on the basis of both existing and future agreements between the US and the EU and its Member States, in the field of preventing, investigating, detecting, and prosecuting criminal offenses, including terrorism;

Recognizing that certain existing agreements between the Parties concerning the processing of personal information establish that those agreements provide an adequate level of data protection within the scope of those agreements, the Parties affirm that this Agreement should not be construed to alter, condition, or otherwise derogate from those agreements; noting however, that the obligations established by Article 19 of this Agreement on judicial redress would apply with respect to all transfers that fall within the scope of this Agreement, and that this is without prejudice to any future review or modification of such agreements pursuant to their terms.

Acknowledging both Parties’ longstanding traditions of respect for individual privacy including as reflected in the Principles on Privacy and Personal Data Protection for Law Enforcement Purposes elaborated by the EU-U.S. High Level Contact Group on Information Sharing and Privacy and Personal Data Protection, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and applicable EU laws, the United States Constitution and applicable U.S. laws, and the Fair Information Practice Principles of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; and

Recognizing the principles of proportionality and necessity, and relevance and reasonableness, as implemented by the Parties in their respective legal frameworks;

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE AGREED AS FOLLOWS:

Article 1: Purpose of the Agreement

- The purpose of this Agreement is to ensure a high level of protection of personal information and enhance cooperation between the United States and the European Union and its Member States, in relation to the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offenses, including terrorism.

- For this purpose, this Agreement establishes the framework for the protection of personal information when transferred between the United States, on the one hand, and the European Union or its Member States, on the other.

- This Agreement in and of itself shall not be the legal basis for any transfers of personal information. A legal basis for such transfers shall always be required.

Article 2: Definitions

For purposes of this Agreement:

- “Personal information” means information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. An identifiable person is a person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, by reference to, in particular, an identification number or to one or more factors specific to his or her physical, physiological, mental, economic, cultural or social identity.

- “Processing of personal information’7 means any operation or set of operations involving collection, maintenance, use, alteration, organization or structuring, disclosure or dissemination, or disposition.

- “Parties” means the European Union and the United States of America.

- “Member State” means a Member State of the European Union.

- “Competent Authority” means, for the United States, a U.S. national law enforcement authority responsible for the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offenses, including terrorism and, for the European Union, an authority of the European Union, and an authority of a Member State, responsible for the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offenses, including terrorism.

Article 3: Scope

- This Agreement shall apply to personal information transferred between the Competent Authorities of one Party and the Competent Authorities of the other Party, or otherwise transferred in accordance with an agreement concluded between the United States and the European Union or its Member States, for the prevention, detection, investigation and prosecution of criminal offences, including terrorism.

- This Agreement does not affect, and is without prejudice to, transfers or other forms of cooperation between the authorities of the Member States and of the United States other than those referred to in Article 2(5), responsible for safeguarding national security.

Article 4: Non-Discrimination

Each Party shall comply with its obligations under this Agreement for the purpose of protecting personal information of its own nationals and the other Party’s nationals regardless of their nationality, and without arbitrary and unjustifiable Discrimination.

Articie 5: Effect of the Agreement

- This Agreement supplements, as appropriate, but does not replace, provisions regarding the protection of personal information in international agreements between the Parties, or the United States and Member States that address matters within the scope of this Agreement.

- The Parties shall take all necessary measures to implement this Agreement, including, in particular, their respective obligations regarding access, rectification and administrative and judicial redress for individuals provided herein. The protections and remedies set forth in this Agreement shall benefit individuals and entities in the manner implemented in the applicable domestic laws of each Party. For the United States, its obligations shall apply in a manner consistent with its fundamental principles of federalism.

- By giving effect to paragraph 2, the processing of personal information by the United States, or the European Union and its Member States, with respect to matters falling within the scope of this Agreement, shall be deemed to comply with their respective data protection legislation restricting or conditioning international transfers of personal information, and no further authorization under such legislation shall be required.

Article 6: Purpose and Use Limitations

- The transfer of personal information shall be for specific purposes authorized by the legal basis for the transfer as set forth in Article 1.

- The further processing of personal information by a Party shall not be incompatible with the purposes for which it was transferred. Compatible processing includes processing pursuant to the terms of existing international agreements and written international frameworks for the prevention, detection, investigation or prosecution of serious crimes. All such processing of personal information by other national law enforcement, regulatory or administrative authorities shall respect the other provisions of this Agreement.

- This Article shall not prejudice the ability of the transferring Competent Authority to impose additional conditions in a specific case to the extent the applicable legal framework for transfer permits it to do so. Such conditions shall not include generic data protection conditions, that is, conditions imposed that are unrelated to the specific facts of the case. If the information is subject to conditions, the receiving Competent Authority shall comply with them. The Competent Authority providing the information may also require the recipient to give information on the use made of the transferred information.

- Where the United States, on the one hand, and the European Union or a Member State on the other, conclude an agreement on the transfer of personal information other than in relation to specific cases, investigations or prosecutions, the specified purposes for which the information is transferred and processed shall be further set forth in that agreement.

- The Parties shall ensure under their respective laws that personal information is processed in a manner that is directly relevant to and not excessive or overbroad in relation to the purposes of such processing.

Article 7: Onward Transfer

- Where a Competent Authority of one Party has transferred personal information relating to a specific case to a Competent Authority of the other Party, that information may be transferred to a State not bound by the present Agreement or international body only where the prior consent of the Competent Authority originally sending that information has been obtained.

- When granting its consent to a transfer under paragraph 1, the Competent Authority originally transferring the information shall take due account of all relevant factors, including the seriousness of the offence, the purpose for which the data is initially transferred and whether the State not bound by the present Agreement or international body in question ensures an appropriate level of protection of personal information. It may also subject the transfer to specific conditions.

- Where the United States, on the one hand, and the European Union or a Member State on the other, conclude an agreement on the transfer of personal information other than in relation to specific cases, investigations or prosecutions, the onward transfer of personal information may only take place in accordance with specific conditions set forth in the agreement that provide due justification for the onward transfer. The agreement shall also provide for appropriate information mechanisms between the Competent Authorities.

- Nothing in this Article shall be construed as affecting any requirement, obligation or practice pursuant to which the prior consent of the Competent Authority originally transferring the information must be obtained before the information is further transferred to a State or body bound by this Agreement, provided that the level of data protection in such State or body shall not be the basis for denying consent for, or imposing conditions on, such transfers.

Article 8: Maintaining Quality and Integrity of Information

The Parties shall take reasonable steps to ensure that personal information is maintained with such accuracy, relevance, timeliness and completeness as is necessary and appropriate for lawful processing of the information. For this purpose, the Competent Authorities shall have in place procedures, the object of which is to ensure the quality and integrity of personal information, including the following:

(a) the measures referred to in Article 17;

- where the transferring Competent Authority becomes aware of significant doubts as to the relevance, timeliness, completeness or accuracy of such personal information or an assessment it has transferred, it shall, where feasible, advise the receiving Competent Authority thereof;

- where the receiving Competent Authority becomes aware of significant doubts as to the relevance, timeliness, completeness or accuracy of personal information received from a governmental authority, or of an assessment made by the transferring Competent Authority of the accuracy of information or the reliability of a source, it shall, where feasible, advise the transferring Competent Authority thereof.

Article 9: Information Security

The Parties shall ensure that they have in place appropriate technical, security and organizational arrangements for the protection of personal information against all of the following:

- accidental or unlawful destruction;

- accidental loss; and

- unauthorized disclosure, alteration, access, or other processing.

Such arrangements shall include appropriate safeguards regarding the authorization required to access personal information.

Article 10: Notification of an information security incident

- Upon discovery of an incident involving accidental loss or destruction, or unauthorized access, disclosure, or alteration of personal information, in which there is a significant risk of damage, the receiving Competent Authority shall promptly assess the likelihood and scale of damage to individuals and to the integrity of the transferring Competent Authority’s program, and promptly take appropriate action to mitigate any such damage.

- Action to mitigate damage shall include notification to the transferring Competent Authority. However, notification may: (a) include appropriate restrictions as to the further transmission of the notification; (b) be delayed or omitted when such notification may endanger national security;(c) be delayed when such notification may endanger public security operations.

- Action to mitigate damage shall also include notification to the individual, where

appropriate given the circumstances of the incident, unless such notification may endanger: (a) public or national security;(b) official inquiries, investigations or proceedings;(c) the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution of criminal offenses;(d) rights and freedoms of others, in particular the protection of victims and witnesses. - The Competent Authorities involved in the transfer of the personal information may consult concerning the incident and the response thereto.

Article 11: Maintaining Records

1, The Parties shall have in place effective methods of demonstrating the lawfulness of

processing of personal information, which may include the use of logs, as well as other forms of records.

- The Competent Authorities may use such logs or records for maintaining orderly operations of the databases or files concerned, to ensure data integrity and security, and where necessary to follow backup procedures.

Article 12: Retention Period

- The Parties shall provide in their applicable legal frameworks specific retention periods for records containing personal information, the object of which is to ensure that personal information is not retained for longer than is necessary and appropriate. Such retention periods shall take into account the purposes of processing, the nature of the data and the authority processing it, the impact on relevant rights and interests of affected persons, and other applicable legal considerations.

- Where the United States, on the one hand, and the European Union or a Member State on the other, conclude an agreement on the transfer of personal information other than in relation to specific cases, investigations or prosecutions, such agreement will include a specific and mutually agreed upon provision on retention periods.

- The Parties shall provide procedures for periodic review of the retention period with a view to determining whether changed circumstances require further modification of the applicable period.

- The Parties shall publish or otherwise make publicly available such retention periods.

Article 13: Special Categories of Personal Information

- Processing of personal information revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions or religious or other beliefs, trade union membership or personal information concerning health or sexual life shall only take place under appropriate safeguards in accordance with law. Such appropriate safeguards may include: restricting the purposes for which the information may be processed, such as allowing the processing only on a case by case basis; masking, deleting or blocking the information after effecting the purpose for which it was processed; restricting personnel permitted to access the information; requiring specialized training to personnel who access the information; requiring supervisory approval to access the information; or other protective measures. These safeguards shall duly take into account the nature of the information, particular sensitivities of the information, and the purpose for which the information is processed.